This essay received an HD (high distinction) from my tutors at Monash.

1. Introduction

I have chosen to compare the high-school Chemistry curricula of China and Wales.

1.1 Rationale for choosing these two curricula

China has been a part of my life for a long time. I have no Chinese heritage but have had a strong appreciation of Chinese culture since I was 16. I’ve travelled through China, worked in Chinese schools for 3 years, married a Chinese woman and we now live in Australia with 5 other Chinese people. I’m constantly looking for new aspects of Chinese culture to explore, and this assignment was an exciting opportunity to do just that. Choosing to research the Chinese Chemistry curriculum was a very easy choice for me to make.

I chose the Welsh curriculum because I grew up there and studied their curriculum (called WJEC) during high school. By examining the Welsh curriculum, I intended to highlight any ‘gaps’ with respect to the Australian Curriculum that I will be teaching next year. I recall the WJEC Chemistry curriculum as being comprehensive but highly theoretical with little reference to society or industry.

Both of these curricula are directly relevant to me. Comparing the curriculum of a de-industrialised “developed” Wales with that of a highly-industrialised, “developing” China was a fascinating exercise. Even though China and Wales are both very nationalistic and are both ‘socialist’ to some extent, their high-school Chemistry curricula are show striking differences. Curricula reflect the societies they are intended to serve (Noddings, 2009).

1.2 Nomenclature

The official names for these curricula are “全日制普通高级中学化学教学大纲” and “WJEC Chemistry GCE A/AS Specification 2009-2010”. For the reader’s convenience, I refer to them as “Chinese” and “Welsh” curricula throughout this document, respectively. The original Chinese curriculum is written in Chinese, and I translated the excerpts in this essay myself.

2. Focus

In this section, I evaluate the thinking behind the development of each curriculum.

2.1 Similarities

The Chinese and Welsh curricula are about 80% similar in scope. Atomic structure is the first topic in each case, probably because it provides a foundation for all the later topics. Appendix 1 shows that 16 of the 22 topics in the Chinese curriculum were also covered in the Welsh curriculum, and 17 of the 20 topics in the Welsh curriculum were also covered in the Chinese curriculum (differences in topic structure explain the mismatch). The Chinese and Welsh curricula put similar emphasis on practical experiments (15% of classes vs 20% of final grade, respectively) and both curricula ask teachers to make greater use of ICT in the classroom.

2.2 Differences

The Chinese and Welsh curricula differ in depth, sequence and structure.

2.2.1 Depth

Despite having similar scopes, the Chinese curriculum goes much deeper into most topics, particularly at the “elective” level. The Welsh curriculum goes deeper in only a few niche areas—notably enthalpy, VSEPR theory and spectroscopy. Suggested experiments in the Chinese curriculum tend to mimic industrial processes and quality control checks, whereas the Welsh curriculum suggests no practical activities at all (the nature of the externally-assessed practical is kept secret until examination day).

2.2.2 Sequence

Topics in the Chinese curriculum are ordered more logically. For example, topics on chemical equilibria, ions in solution, redox, batteries and electrolysis are written sequentially in that order—a very logical progression. The Chinese curriculum then progresses through the periodic table from right to left (from group 17 to group 1), which also makes good logical sense. In contrast, the Welsh curriculum follows no logical sequence. For example, atomic structure, equilibia, energetics, molecular bonding, and periodicity are taught in that order. My own Chemistry teacher was kind enough to rearrange it for us when I was in high school.

2.2.3 Structure

The illogical sequence of the Welsh curriculum could be explained in part by the structural constraints that result from having a two-part course (the two parts are named AS-level and A-level, and each is a separate one-year qualification). In the Chinese curriculum, however, Chemistry is compulsory. Students can choose between an easier “compulsory Chemistry” (called 化学I) and a more challenging “elective Chemistry” (called 化学II), but both courses are three years long, and both courses are identical in the first year. Students typically choose between the “compulsory” and “elective” options at the end of the first year. The Chinese curriculum is free of the Welsh structural constraints, and is thus able to follow a more logical order.

2.3 Why these topics?

The Chinese curriculum is written for students who will likely work in factories at some point in their adult lives. By adopting Michael Apple’s thesis that curricula are written from a class perspective, we can see that the Chinese curriculum is written from the view of an industrious proletariat, who have been considered “vanguards of the revolution” since the Communist revolution in 1949 (Apple, 2004).

Geographically, Wales is a stark contrast to China. The population is only 3 million (vs 1.3 billion), mostly rural (81% vs 48%), and, unlike China, the huge mining industry of the 20th century is now a relic of the past. Industry is so sparse in Wales that there would be no pressure from an industrial sector to write industrial relevance into the curriculum. The WJEC also has no reason to train students vocationally for a non-existent chemical industry. In my opinion, Welsh students study A-level Chemistry principally because it is a pre-requisite for acceptance into scientific subjects at university—most of which are located in neighbouring England.

3. Implicit and Explicit Messages

In this section, I explore the philosophies conveyed by the Welsh and Chinese curricula. These two curricula differ greatly in their intended effects on society. The stated “aims” in the Welsh curriculum are concise, limited and “politically-correct”, while the stated aims in the Chinese curriculum are repetitive, highly ambitious and laden with Marxist vocabulary. In this section, I will explore three aspects of these differences: length, breadth and literary tone. I use “aims” in the same sense as defined by Noddings (2009).

3.1 Breadth of the ‘rationale’ section

The Welsh ‘rationale’ section (comprising only 3% of the document) gives only one reason for studying Chemistry: to become a chemist. UK Census data show that most high-school graduates leave Wales to pursue further education or employment—presumably in England or overseas. Despite Welsh government initiatives to boost applications for Welsh universities (e.g. no tuition fees, preferential employment), I think the Welsh Chemistry curriculum counteracts this goal by serving as a stepping-stone for Welsh students to pursue their careers in England or elsewhere.

The Chinese ‘rationale’ section (comprising 50% of the document) is broader than its Welsh counterpart because the schools to which it applies. Some of these are world-leading high schools with Apple iPad programs (Affiliated High School of Renmin University; Apple.com), while others are remote village schools lacking permanent classrooms. This dichotomy is reflected in the Chinese curriculum by the way it contains both a minimum prescription of content (to cater to lower-quality schools; section 3) and a beautifully-written licence to innovate (to cater to higher-quality schools; section 5). This approach echoes James (1899/2001), who wrote that pedagogy is “both a science and an art”. This dialectical approach (a mixture of Thorndike and Dewey) is typical of many Chinese policy documents—not just their Chemistry curriculum (Heilmann, 2008).

3.2 Literary tone of the ‘rationale’ section

The Chinese “rationale” section is peppered with patriotic, Marxist and Maoist phrases throughout:

- 今后参加社会主义建设

“from this day forward participate in socialist construction [of society]” - 进行辩证唯物主义观点的教育

“adopt a dialectical materialist view of education” - 实事求是

“Seek truth from facts” — a famous quote by Chairman Mao - 热爱家乡

“foster a deep love for their hometown” — a very Chinese phenomenon

Furthermore, the stated purpose of the curriculum goes beyond individual benefit:

- 我国的社会主义建设事业需要大批富有创新精神的建设人才

“The socialist construction of our motherland requires a large number of innovative, well-spirited, highly-talented people”

- 实验教学中要注意对学生进行团结、合作、安全、爱护仪器、节约药品等教育…

“Experimental teaching should focus on students’ unity, co-operation, safety, ability to use instruments with care, and the frugal use of medicines…” - Patriotic forms such as 祖国 (“ancestral land”) and 我国 (“my/our land”) are used instead of the more standard 中国 when referring to “China”.

China has a long history of writing policy documents in poetic, ideological language. In ancient China, acceptance for life tenure in official palaces was dependent on the essay-writing and calligraphical ability of the applicants. Even today, high-level politicians gain kudos with the public when they publicly demonstrate their ability to write high-quality essays using calligraphy (Xinhuanet.com, 2009). The Chinese curriculum document and many other policy documents reflect this centuries-old tradition.

This is a stark contrast to the Welsh version, which strives to take culture out of the curriculum completely:

“this curriculum is equally accessible to all irrespective of… cultural background”.

The Welsh version makes no references to society or to the ‘greater good’ whatsoever. The largest sections of the document are “content” and “assessment”. This bland rationale is indicative of a de-industrialised society with a small government, where, in stark contrast to China, nationalism and governance are not directly linked. The Welsh curriculum serves the interest of the people who study it, whereas the Chinese curriculm serves the interests of both the people and the state.

4. Aims and Outcomes

4.1 Bloom’s Taxonomy

China’s Chemistry curriculum makes implicit references to the first three levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy. The Bloom level required for each sub-topic is written into the curriculum according to the following key:

The Welsh curriculum also makes references to Bloom’s Taxonomy but in a slightly different way. Each sub-topic begins with a verb that could be categorised as remembering, understanding, applying or analysing. Here are some examples:

Neither curriculum requires the upper three levels of Bloom’s taxonomy, “analysing”, “evaluating” or “creating”.

4.2 Constructivism

The Chinese curriculum makes reference to constructivism in the phrase:

学生掌握知识、技能和形成能力,是一个循序渐进、由低级向高级发展的过程

“The knowledge and skills that students acquire are sculpted over time from junior to senior levels”.

The Welsh curriculum makes no direct references to constructivism, nor is it implied from the sequence of units in the curriculum.

4.3 Behaviourism as a teaching method

The Chinese curriculum describes practical experiments and provides videos that could accompany each topic. Almost all of the practical experiments on the list have direct links with industrial production. Here are some examples:

- Making soap

- Production and purification of ethylene

- Determination of iodine content in kelp

- An investigation into electrochemical corrosion of batteries

It also tells teachers to speak at an appropriate pace, to announce the steps of the experiment and provide clear explanations as they go along. It tells them to follow good safety rules and even provides lists of equipment that all students will be expected to know how to use (e.g. test tube, test tube rack, and many more).

5. Discussion

A good curriculum prepares students for lifelong learning in a structured, reliable way. It caters to a set of “aims”, which are appropriate for the society where it is taught (Noddings, 2009). Meanwhile, a good teacher will make the curriculum useful and relevant to the students’ lives (Ayers & Ayers, 2011). My evaluation of these two curricula shows that both of them meet these standards in ways that are appropriate for the societies that they serve (Noddings, 2009).

China’s high school system produces 10 million graduates each year, nearly 6 million of whom will enter university or vocational training. The vast majority of the remainder will find employment—many in industry—and the Chinese Chemistry curriculum provides them with a solid practical foundation for this. By being compulsory and having nationwide coverage, the Chinese curriculum serves not only the Chinese students who study it, and the Chinese industries that benefit from it, but also the Chinese state that has, for thousands of years, placed a remarkably high value on long-term national unity (Noddings, 2009).

On the other hand, the Welsh Chemistry curriculum does not serve the interests of the state: it only serves the needs of young people who want to leave Wales to find work. The Welsh curriculum lacks industrial relevance and makes no attempt at social engineering, which reflects both the Welsh economy and the Welsh “small government” ideology, respectively. The Welsh curriculum, for me, simply served as a stepping-stone to the University of Cambridge in 2006.

Thank you for reading.

Links to curriculum documents

Chinese curriculum, “全日制普通高级中学化学教学大纲” is available at: http://www.hzxjhs.com/jiaoyanzu/huaxue/request.php?action=attachment&id=57

Welsh curriculum, “GCE Chemistry Specification 2009-2010” is available at: http://www.wjec.co.uk/uploads/publications/6148.pdf

References

Apple, M., (2004). Ideology and Curriculum. Routledge Press.

Apple.com. One school in China takes an innovative approach to education. Retrieved from: http://www.apple.com/education/profiles/rdfz/#video-rdfz

Ayers, R. and Ayers, W. (2011) ‘Coda’ In Teaching the taboo: courage and imagination in the classroom. Teachers College, New York, pp. 123-127

Gibboney, R. A., (2006). Intelligence by Design: Thorndike versus Dewey. The Phi Delta Kappan 88(2):170–172

Heilmann, S., (2008). Policy Experimentation in China’s Economic Rise. St Comp Int Dev 43, 1–26.

James, W. (1899/2001). Talks to teachers on Psychology and to Students on Some of Life’s Ideals. New York: Dover Press.

Luke, A., (2003). Teaching after the Market: From the Commodity to Cosmopolitanism. In Alan Reid and Pat Thomson (eds). Towards a Public Curriculum. Australian Curriculum Studies Association Inc. Deakin West, ACT: Post pressed, pp.139-155.

Noddings, N., (2009). The Aims of Education. In David Flinders and Stephen Thornton (eds). The Curriculum Studies Reader (3rd edition). New York: Routledge, pp.425-438.

Tomlinson, S. (1997). Edward Lee Thorndike and John Dewey on the Science of Education. Oxford Review of Education 23(3):365–383

Xinhuanet.com (2009, October 14). 新华社副总编辑:总理对我说《文责自负》. 新华网Retrieved from http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2009-10/14/content_12227173.htm

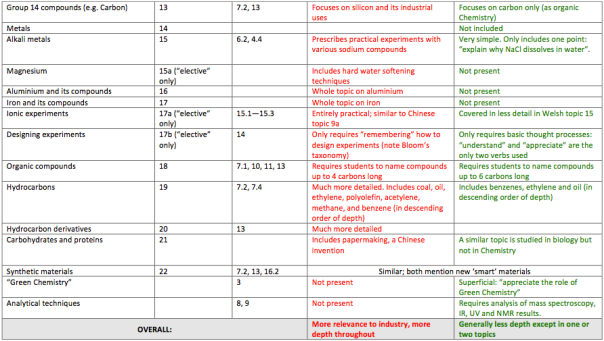

Appendix 1: Comparisons of Welsh and Chinese Chemistry Curricula by Topic

Related articles

- ‘A third of the school curriculum should be taught in Welsh’ call (schoolsimprovement.net)

- ‘A third of the school curriculum should be taught in Welsh’ call (walesonline.co.uk)

- Online Study Guides for the SAT Chemistry Subject Test (college.answers.com)

- Too Cool for School? Comparing Danes with Chinese… (noneofyourbizz.wordpress.com)

The University of Melbourne, Science Degrees, for example, accept students with a study score of at least 25 (but this is a minimum – don’t rely on that figure – more like 30 plus) and has completed VCE Units 3 and 4 in Chemistry. This makes finding a good Chemistry tutor in Melbourne all the more important. Read more here: http://bit.ly/1kVtWLB

LikeLike

i would like to provide me with essentials for Chinese translation…

Dr.Ali Foda

LikeLike