The essay below was written by GPT-2, an AI writing bot. I typed the first sentence in blue… and the machine wrote the entire rest of the essay.

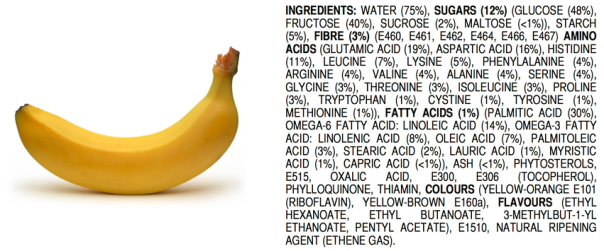

Chemophobia is defined as the irrational fear of compounds perceived as synthetic. Some people feel like they are being sprayed with an unknown chemical, and their eyes, nose, and skin are inflamed, burning, and itchy. This fear of unknown chemicals has led to several incidents where people have reported being exposed to chemicals they thought were harmless.

The fear of synthetic chemicals is not new, but it has recently increased in popularity. The concern about synthetic chemicals has been exacerbated by a rise in sales of synthetic fragrances, cosmetics, and personal care products. This is partly because companies can now make chemicals that do not have to be tested for safety before they are marketed.

The term ‘synthetic’ is often used as a blanket term for any chemical with an unknown origin. The American Chemical Society, a scientific and professional organization based in the US, defines synthetic as an “electronic or chemical compound that is produced artificially” and is “comparable to a natural molecule” but with the added ability to be made more stable, more potent, and more easily manufactured. These synthetic chemicals, which include plastics, fragrances, pharmaceuticals, and other everyday items, are the latest and the greatest in the war against nature and the destruction of the environment, and we are witnessing their impact in the lives of our most vulnerable citizens.

In order to be considered as synthetic, the chemical must meet one of two criteria. First, the chemical must have been produced artificially. A drug that is made by genetically engineered organisms is a synthetic chemical. Another example is a chemical used to make certain pharmaceuticals, including the antibiotics used in humans.

A third definition of synthetic is that the chemical is synthetically produced. This means that the chemical is not naturally occurring or derived from a naturally occurring source.

The Food and Drug Administration is responsible for approving or withholding approval of substances for use in food. This includes both foods and drug products. The FDA will consider many factors in determining whether a substance is a drug or food. These include, but are not limited to: the presence of the substance in the food or drug product, the strength, purity, potency, and composition of the substance; and whether it is necessary for the safety and efficacy of the food or drug product.

A drug must have been approved by the FDA. It is also important to note that if a substance is being used to treat a particular disease or condition, the FDA has the authority to regulate the use of that medication to protect the health and safety of those taking it.

If a drug or food is used in the treatment of cancer or to increase fertility, the FDA may require that the substance be registered for those purposes.

Synthetic chemicals are considered safe by the EPA. Natural chemicals are considered safe to drink. This is a good thing, in my opinion, but there are no tests to prove it. We have no way to know that they are safe to use, and we have no way to know that they aren’t.

When you read the labels on all of the chemicals found in pesticides, you’ll be left with a feeling that you’re eating poison.

In the book ‘Walking Through Toxic Walls,’ author and toxicologist Michael Dourson describes the effects of pesticide residues on humans. He writes that:

“Even low concentrations of pesticide residues are toxic and can cause chronic effects such as infertility, cancer, and reproductive dysfunction. We are all exposed to the same chemical cocktails in our everyday lives, and if any of them cause harm, we need to know about it. We need to be sure we are eating safe foods, using safe cleaners, or using safe household chemicals.”

For some people, organic is not sufficient. They want to be sure their food is healthy, and they want to make sure they are using clean, safe products. Some organic products are organic in name only, and they do not guarantee the quality of the product. The USDA Organic seal is an imperfect means of ensuring product quality, but many people still want to use organic because it means they are doing what’s right for the Earth.

Organic foods are not necessarily healthier. This is why we believe in “Food for Thought.” If you think about your food choices and where you are spending your money, you are spending too much on foods that are processed or chemical laden. And we all know that junk food is just not good for us. So how do you choose to buy organic food?

Our website has a list of organic produce stores, and many of them offer a large variety of organic products. You can click on the logo of any of these stores to learn more about what they offer. The links to the stores are listed in the green bar below, in the “Organic Products” section. You can also check out our list of recommended organic food places and blogs to help you find organic foods closer to home.

(Written by GPT-2, an AI writing machine.)